Last week, I wrote about the hard problem of consciousness which is the perplexing phenomena that some physical processes (i.e., brains) give rise to conscious experience while others do not. I also the question of whether a philosophical 'zombie' could exist—a being physically identical to another human, behaving exactly how humans behave but with no consciousness. I concluded that such a zombie is theoretically possible given that consciousness has no known biological function and likely doesn't affect our behavior in ways that our intuition might suggest.

Indeed, neuroscience might one day (far in the future) find the neural correlates for every human behavior and be able to predict our behavior and affect based on our brain activity with 100% accuracy. While looking at a red apple, scientists might one day be able to predict that I am looking at a red apple based on my neuron activity alone. It would be an amazing scientific achievement and is an end worth pursuing.

Still, though, this newfound scientific achievement wouldn't be able to tell me about what it is like to look at a red apple. Consciousness is a subjective experience and thus by definition science is seemingly locked out of the room.

Yet this hasn't stopped theorists from looking for solutions to the hard problem of consciousness. One such solution is a theory known as panpsychism which states that consciousness is a fundamental property of all matter. There are many different forms of panpsychism, but the most common form is constitutive micropsychism which is the view that the smallest parts of one's brain has some form of consciousness and the rich and complex conscious experience of humans is a result of the sum of its parts. Consequently, consciousness is less realized in dogs/cats, less so in insects, and so on until atoms and electrons.

Panpsychism is a deeply unintuitive view of the world around us, yet it can't be ignored in debates about the origin consciousness. For one, it has the advantage of being a simple and eloquent explanation of the hard problem of consciousness. Occam's razor is a philosophical principle that states that the simplest solution is almost always the best. If consciousness is not fundamental to all matter, then there is a time when matter makes a large leap from just 'stuff' to 'stuff with experience', and this phenomenon is inherently anti-scientific.

Some have tried to discredit panpsychism by construing it within seemingly ridiculous questions such as "is a rock conscious?"—as if panpsychism is proposing that rocks have a phenomenological experience on the order of humans. But panpsychism isn't claiming this at all—only that the atomic particles that makeup rocks have the same properties of consciousness that you and I have.

Still, panpsychism is still considered to be an unconventional and fringe theory and many neuroscientists today believe that consciousness arises from some yet unidentified complex process in the brain and that by studying the brain we will understand consciousness better.

Moreover, if we are to accept the unintuitive view of panpsychism, we also have to accept perhaps an even more unintuitive view: that multiple consciousnesses exist within one body. If a worm has some kind of low-level consciousness, then why wouldn't my liver (which is in some ways more complex than a worm) also have some kind of consciousness?

Thus, panpsychism today has a combinatorial problem: How do billions of low-level consciousnesses give rise to one coherent consciousness within each of us?

Personally, I find panpsychism a difficult theory to accept and remain unconvinced. At the moment, I am persuaded by the view that consciousness exists only within complex brains and is a result of an extremely complicated integrative processing of our senses and perceptions. Still, though, the question of why consciousness exists remains and so I am at least open to arguments surrounding panpsychism.

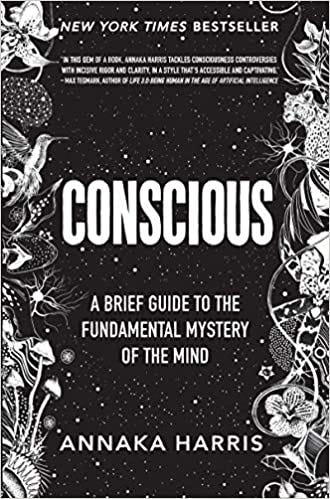

📚 Book Recommendation

If the last two editions of Synapse have ignited your interest in the subject of consciousness, then I highly recommend the book Conscious by Annaka Harris. It’s a short (~100 pages) and accessible introduction to this topic that is eloquently written and fascinating. It has been influential in my interest in neuroscience generally and is one of the many inspirations for this newsletter.

🔗 Links

To illustrate just how contested the subject of panpsychism is, here are two juxtaposed articles: Why Panpsychism Is Probably Wrong from the Atlantic and Panpsychism is Crazy, But It’s Also Most Probably True from Phillip Goff.

Why obeying orders can make us do terrible things. Many of the greatest atrocities of human history were performed by ordinary, cognitively normal human beings. A new neuroimaging study has attempted to link the act of obeying orders to our capacity for empathy.

Brain patterns indicative of consciousness in unconscious patients. One of the most important areas of consciousness research from a clinical perspective is how to know externally the state of a patient’s consciousness. New research in this area may help doctors understand what to do for patients in the case of brain death.

🙏 Thank You!

I’ve received a lot of amazing feedback in the first month of Synapse and am incredibly grateful for it. I’m ultimately writing this for myself, but it’s nice that some people actually read it and are enjoying it. As always, don’t hesitate to hit ‘reply’ on this email and start a conversation!

⚡️P.S. If you liked this newsletter, please forward it to friends! If you’re new here subscribe below⚡️

Follow me on Twitter

Connect on LinkedIn

How would you account for elaborate NDEs in an unconscious individual with no physical evidence of brain activity and with subsequent report of viewing an unknown relative (Later confirmed by someone), or a prediction (cf. Mary Neal) that later is true?