Your Inner Eye

Synapse #9: A possible function of consciousness

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the puzzling nature and function of consciousness. Given that we have no idea how consciousness arises out of brain matter, maybe it would be useful to know the contribution of consciousness to our functioning. However, as I outlined, despite our best efforts, some have argued that consciousness seemingly plays no role in our behavior. It doesn’t seem to be required for sensing and responding to our environment, for thinking generally, or even for a sense of self. That is, despite our best intuitions, what we call consciousness seems to be a superfluous or otherwise vestigial function of our brain.

We can have debates about where we draw the consciousness line, whether it be at a monkey, dog, cricket, or worm, but whatever the line, consciousness arose at some point in the evolutionary history of animals. According to the basic theory of evolution, biological functions that spontaneously arise, either accidentally or otherwise, typically don’t stick around unless they improve the reproductive fitness of the animal (or at least don’t actively harm the organism). Thus, it might be worthwhile to look at consciousness from an evolutionary perspective.

Consciousness as an evolved property

The field of sociology has for decades sought to understand the complex social dynamics of the human race. If one takes a moment to consider the incredible talent that a human must have to be reproductively successful, it is quite striking. Humans must have the ability to understand, respond to, and manipulate the behavior of others. We have to read body language, fit into our social group, and ultimately be cooperative. Broadly speaking, humans’ social skills is one of the main reasons for our success as a species.

Given this social need, neuropsychologist Nicholas Humphrey has argued that humans in particular have evolved consciousness as a way to meet our formidable need to understand others. To demonstrate how consciousness could absolutely be required for this skill, let us first imagine what it would be like to do this without the help of consciousness.

Your Outer Eye

If we had no consciousness, and therefore no experience of what it is like “from the inside” we would be tasked with understand our fellow humans from an outside perspective. Lucky for us, behavior psychology has been trying to do this for decades and thus gives us insight into whether this would be possible. Broadly speaking, behavioral psychology is based on the assumption that we can learn about the human mind by observing behavior. However, one thing we’ve learned in a century of this research is that this is simply impossible. Sure, humans generally behave according to a few special laws, but by and large, humans have feelings and these feelings make for a puzzling explanation of our mind from the outside. From Humphrey:

I now realize, that in dismissing these feelings as if they were a kind of scientific nuisance, the behaviorists were dismissing the most powerful tool imaginable for making sense of human lives

Our difficulty relying on our Outer Eye can also be demonstrated with this example. Why am I writing this newsletter at this moment? It might be because enough motivation has bubbled up in my consciousness to propel my writing or maybe I’m looking forward to the pleasure I get from hitting the “publish” button. Now I’m feeling like I want to get up for a glass of water, but I know that writing is going really well right now and I don’t want to interrupt that. Ugh, I now realize that it’s been an hour and I was hoping to get laundry done before now… drat…

This internal monologue wasn’t a particularly complicated scenario, and I’m sure you had no trouble understanding my various urges and thoughts as they entered my mind. But imagine explaining my situation to someone who has no idea what it is like to be “on the inside.” Everything from empathy to a basic understanding of feelings, emotions, or “gut” reactions would be infinitely more difficult. Thus Humphrey has proposed an inward-looking neural process, one that is clearly advantageous and would have stuck around in the evolutionary train: your inner eye.

Your Inner Eye

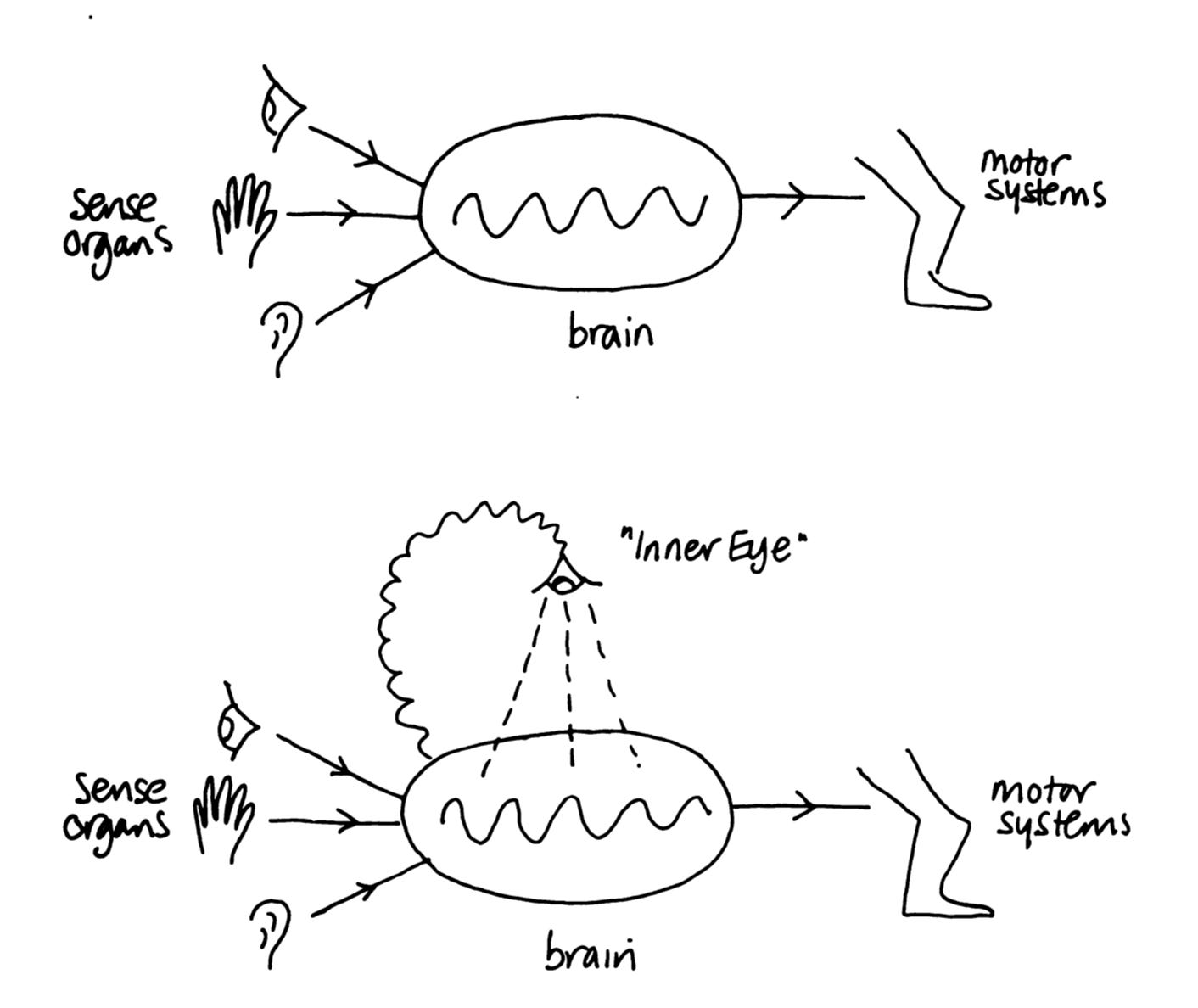

You can probably easily imagine an animal without an inner eye—it’s what is probably your view of all basic animals. There are sensing organs that can detect their local environment, a motor output system that lets the animal move, and an information integration center that makes sense of these systems and computes reactions to various stimuli. This is what some have called the “unconscious cartesian machine.”

Now imagine that another system evolves—one that can view the inside in addition to the outside—a surveyor of not only ourselves but what it is like to be ourselves. It’s easy to see the advantages of such a system: awareness of one’s thought processes, perception accompanied by sensation, and emotion accompanied by feelings.

An inner eye gives us a head start on what makes us tick. The reading of our own mind gives us insight into others. With an inner eye, there isn’t a period of guessing, taking notes on other’s behavior, or constructing models of how people work so that we can live in harmony together.

As a side note: I’ve realized that the process I just outlined above is similar to what many individuals with autism spectrum disorder face. Often these individuals have to learn traditionally what others take for granted (i.e., basic social skills). This makes me wonder that, if Humphrey’s inner eye hypothesis were true, the neural processes that cause autism spectrum disorder might somehow be related to consciousness.

To crystalize how paradigm-shifting an inner eye is, Humphrey lays out a wonderful analogy which I will paraphrase here:

Imagine you live in a house with stairs, a chimney, and candlelight. I can look out at other similar houses on my street and maybe I see smoke billowing up from behind the roof or the flickering of light from some windows. Maybe I see a person appear through a window on a lower floor and then, moments later, through a window on an upper floor. None of this puzzles me because I have a detailed model what the inside of a house is like—that there is such as a thing as stairs, a chimney, and candles. Just imagine what it is like trying to piece together what is going on if you have no conception what could be inside a house. Knowing what a house is like gives me an enormous advantage in not wasting mental energy puzzled by people seemingly floating to the top of houses.

I should note that an explanation of an inner eye does nothing to solve the hard problem of consciousness: how does a brain give rise to experience? But it at least gives what I consider to be a compelling reason for its sustained existence in at least humans and possibly in other animals. A clear, biological function for consciousness possibly hurts the case for panpsychism and further informs our search for the origins of consciousness within brains and not all other matter.

If you’ve made it this far, thanks for spending some time with my thinking and kindly consider forwarding this email to someone in your life who you think might enjoy this newsletter.

🔗 Links

“America First” Will Destroy U.S. Science. Foreign-born scientists make up approximately 50% of U.S. post-doctoral fellows and are responsible for 38% of the Nobel Prizes that have come out of the U.S., yet the current presidential administration is invariably motivated to deter immigration of all kinds—including skilled experts in critical scientific fields for dubious economic reasons.

Simone de Beauvoir on How Chance and Choice Converge to Make Us Who We Are

🤔 #AskSynapse

Do you have a question relating to this week’s issue or any previous issue? Just hit ‘reply’ on this email and I’ll do my best to answer it in an upcoming special #AskSynapse newsletter!

⚡️P.S. If you're new here and want to read more of the Synapse Newsletter each Sunday, subscribe below!⚡️

Attributions

Header Image created by Brian Goff at Vecteezy

Inner Eye Illustration adapted from Nick Humphrey’s The Inner Eye