From "Synapse" to "Overfitted"!

New newsletter from Clayton Mansel

Hey Synapse readers!

I’ve launched a new newsletter called Overfitted, my attempt to cut through the noise in evidence-based medicine. We’ll dissect studies, challenge assumptions, and debate ideas—mostly in Neurology and Alzheimer’s, though not exclusively. If that sounds interesting, subscribe (it’s free):

Synapse was a fun pandemic project on neuroscience, from free will to morality. Since then, I’ve started an MD/PhD and my focus has shifted toward clinical neurology. Writing is thinking, and I’ve missed the conversation. Overfitted is my way back—and a push for more common sense in biomedicine.

To give you a taste, I’ve pasted the first post below. Enjoy!

Current AD Blood Biomarker Studies Miss What's Most Important

What are we optimizing for?

In case you haven’t heard, there are new blood-based assays for Alzheimer’s Disease that detect amyloid and tau in the brain without requiring a brain scan or spinal tap. They are a technical achievement, showing strong correlations with what is going on in the brain.

In my mind, the main advantage of blood biomarkers for AD is that they are less expensive and invasive and are accessible in the primary care setting just like any other blood test. They could, therefore, be revolutionary for Alzheimer’s Disease treatment and care.

So what’s the problem?

We have no idea if they make a difference in outcomes that actually matter to patients.

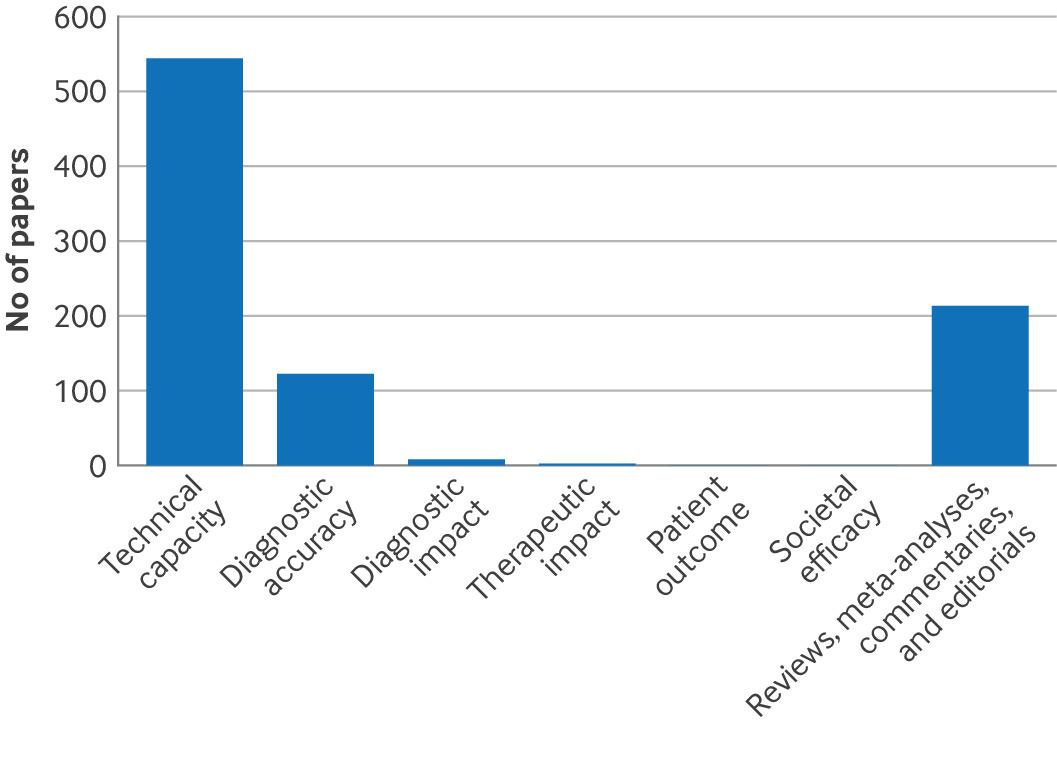

Willem A Van Gool and colleagues just published an excellent review in the BMJ of current AD blood biomarker studies that reveal that nearly every study to date focus on technical and “diagnostic” accuracy without looking at whether patient outcomes are any better.

The “technical capacity” and “diagnostic1 accuracy” of these blood tests are obviously important. But we can imagine what patients are likely to care about: will this test result lead to a better treatment? Will this test result improve my quality of life? We can speculate but we have no idea until we run the trial.

In the optimistic case you could imagine that rolling out these blood tests in primary care could lead to faster referral to a specialist memory center2 and the initiation of the new anti-amyloid therapies.

Or this blood test could overly worry the patient or give him or her a devastating diagnosis earlier in their life for no reason or upside. Life lived not carrying the “Alzheimer’s Disease” diagnosis should count for a lot.

To quote Raffle and Gray “All screening programs do harm. Some do good as well and, of these, some do more good than harm at reasonable cost.”

The “do good” part should be the focus of future AD blood biomarker studies.

“Diagnostic” meaning the presence of amyloid and/or tau in the brain. Neither alone are sufficient for a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease making the term “diagnostic” a bit dubious.

Our memory center gets WAY more referrals than have the capacity to accept