I was wrong about twin studies

Let me clarify....

In the past few weeks I’ve enjoyed digging into Kathryn Paige Harden’s The Genetic Lottery and, thanks to Kathryn’s eloquent and clear writing, realized that I misunderstood how ‘twin studies’ have been used to understand the role of genetics in child development. Here’s what I wrote last month:

One common way to study the impact of genetics on humans is through “twin studies” which compare identical twins (with the exact same DNA sequence) that were separated at birth (and thus have been raised in different “environments”) to fraternal twins (who don’t share a DNA sequence) to estimate the role of genetics in development. Some studies have shown that certain life events are surprisingly correlated between identical twins.

In hindsight, I should have known of course that twins separated at birth are exceedingly rare and so the vast majority of twin studies are actually conducted on twins raised together in their birth home. These studies ask the simple question: how much more similar are identical twins than fraternal twins? Remember that fraternal twins are only 50% genetically similar compared to identical twins which are 100% genetically identical.1

Understanding how these different kinds of twin studies are conducted is important because each method of study comes with its own unique problems. Studying twins separated at birth introduces a host of complications when trying to compare them. Imagine the number of differences in your upbringing between you and your childhood friend. There are thousands and thousands of differences that led to both of you being different, how could you uncover the role of DNA? It would be difficult and those that have tried have brought on much criticism.

Similarly, studying twins raised together asks the question: given equivalent environments, how do the similarities between fraternal and identical twins compare? The “equivalent environments” assumption may not be valid given documented differences in twins’ prenatal environments and parenting. Are identical twins parented in the same way as fraternal twins? I’m suspicious of that assumption.

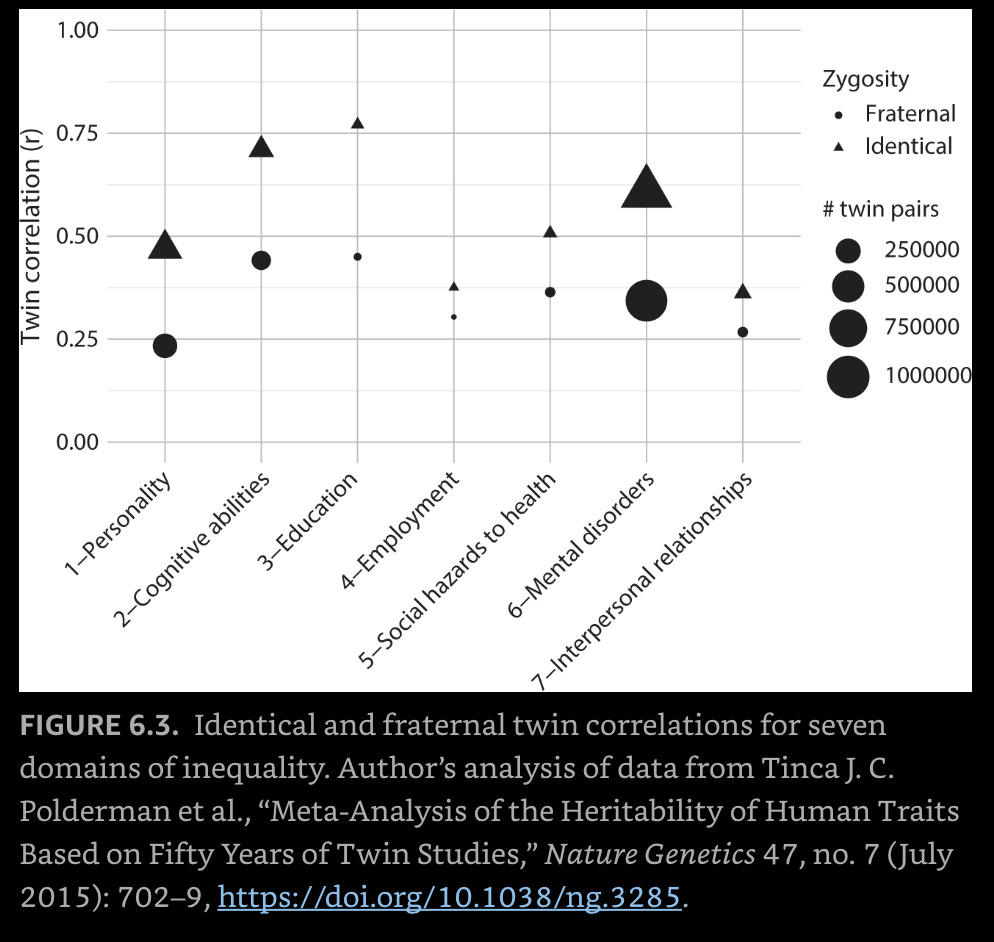

This isn’t to say that we should dismiss 50 years of twin research. The benefit of doing a twin study which simply compares twins between households is that there are a lot more twins to study, and the more you study, the more confident you can be in finding a real effect among the noise. A recent Nature paper conducted what’s called a meta-analysis which is when data is combined from many different studies and analyzed statistically to answer the same question with a lot more power than an individual study. Here’s how Dr. Harden pulled its data from over 2 million twins to compare fraternal to identical twins in seven different life outcomes:

As you can see, in every case, identical twins (triangles) are more correlated with each other than fraternal twins (circles). I like this graphic because it also shows the number of twin pairs that have been studied with the size of the triangles and circles. Bigger shapes means that we can be more confident in the relationship shown on the graph with the highest confidence in correlations in personality and mental disorders.

I hope this was a more fair presentation of this field of research. If you’re like me, you’re left with even more questions than before, and that’s a good thing! That’s what makes studying science so fun. If genetics are a reason for different life outcomes, then a mechanism for this effect would be helpful in convincing me. Dr. Harden has something to say about this and I will be digging into it in the coming weeks.

A brief note on difficult conversations

Here on Synapse we’ve broached controversial and not-so-straightforward topics like free will and morality and one only has to take one look at my Twitter feed to realize that behavioral genetics is another one of those topics that some see as dangerous to values, norms, and the status quo. However, I believe that conversations conducted with an open mind and compassion as first principles can be only productive toward discovering and building a better society. With Synapse I try to broach questions not only because they are interesting intellectually but because I believe they matter. No conversation is too dangerous or controversial to be had given that those first principles are kept, or at least that is my current stance.

I thank all of you for keeping on this wild ride and, please, email me in earnest should you have concerns—I am all ears.

Thanks for reading.

⚡️P.S. If you're new here and want to read more of the Synapse Newsletter twice a month, subscribe below!⚡️

The difference can be a little less than 100% if there are mutations early in life after the two embryos are starting to form. Note also that even though identical twins have the same genes, the expression of those genes is often different due to a large variety of factors. It’s a mess, I know.