The Moral Brain

How does morality work in the brain?

Over the last few months we’ve gone through a meandering journey here at Synapse to uncover the psychological nature of morality in an effort to understand why people make different moral judgements. In Toward a Quest of Understanding, I outlined evidence that our moral decisions are more about our emotional thinking than our rational thinking. Jonathan Haidt likens this phenomenon to the Elephant (emotions) and the Rider (reason). The rider of an elephant often appears to be in charge, but if there is a disagreement between the elephant and the rider, the elephant will win.

Then, in Beyond WEIRD Morality, I wrote about the rather narrow view of morality that the scientific literature portrays. How are we to understand the true nature of morality if the people we use in studies are disproportionally from western, industrial, democratic, and individualistic societies?

Last week, I presented one theory of morality that attempts to be more inclusive of the diverse moral tastes we find in humans across the world (by the way, I’ve gotten lots of great feedback on this piece, so keep sending it in!).

This week, I hope to leverage more neuroscientific studies to fill in gaps about how our moral brain works before moving on to a different topic. So here goes…

How does morality work in the brain?

In 2013, Pascual, Rodrigues, and Gallardo-Pujol reviewed the current neuroscientific research on how the brain modulates moral decision making. From a scientific perspective, this topic is typically studied by presenting subjects with moral dilemmas while scanning the activity going on in their brains. The most famous moral dilemma used in this study is the trolley problem in which subjects are asked to make a choice between killing one person or letting five people die.

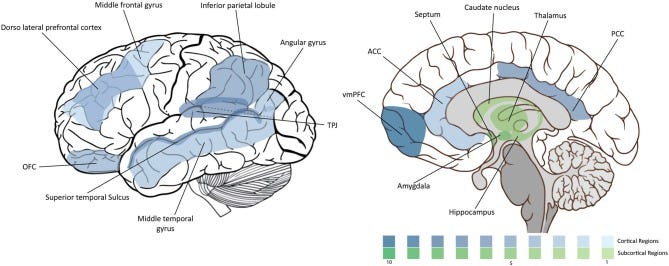

One interesting insight from this review is the implication of two brain areas: the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).1 The VMPFC seems to play a key role in the emtional side of moral judgements. For example, patients with damage to the VMPFC are more likely to endorse a utilitarian solution to a hard moral dilemma.2 The DLPFC, on the other hand, seems to be more strongly activated in rational side of moral judgements. For example, the DLPFC is more strongly activated when making difficult judgments of responsibilities for crimes or during problem-solving.3

Thus, we have two competing brain areas that approach morality in opposite ways—one emotionally (i.e., what feels right?) and one rationally (i.e., what should one do?). The question is: how do these two competing mechanisms interact and how necessary are each of them to moral decision-making?

Psychopaths know right from wrong but don’t care

One way we can study morality in the brain is by studying individuals who are unlucky enough to have a major deficit in an ability to live a moral life: psychopaths. Psychopaths, through no fault of their own, have extreme deficits in many areas including empathy, social savviness, and morality.

Given that the dominant hypothesis in psychology is that emotional processes are absolutely required for basic moral thinking, Cima and colleagues set out in 2010 to test this theory in individuals known to have deficits in both emotional processing and moral behavior.

Interestingly, they found that psychopaths and non-psychopaths made the same judgements when it came to hard moral dilemmas like the Trolley Problem. This result suggests that emotional processing is not required to know right from wrong because psychopaths are just as good as non-psychopaths at knowing the difference.

Nonetheless, psychopaths are much more likely to commit immoral acts. Thus it appears that emotional processing in morality doesn't come into play until a judgement must be translated into a behavior. Psychopaths know right from wrong, they just simply don’t care enough to do anything about it.

So what is the nature of our moral brain?

Overall, I think this neuroscientific research colors our understanding of morality by shedding light on the fact that we really should distinguish between knowing right and wrong and behaving in a moral manner. Like most aspects of human nature, the evidence for the neural underpinnings of morality lie in many different brain areas found all around the brain (see picture above). People have diverse tastes when it comes to what matters around morality and there is a lot more to people’s behavior about morality than just their knowledge of right and wrong.

I hope you’ve enjoyed thinking about this topic as much as I have. As always, if you’ve got expertise or input, please email me or comment below!

Thanks for reading.

⚡️P.S. If you're new here and want to read more of the Synapse Newsletter each Sunday, subscribe below!⚡️

📚 P.S.S. I having forgotten about our Free Will book discussion that I announced here. I am working through the book now (it is admittedly more dense than I thought it would be) and will have more info on this in the coming weeks.

Don’t be afraid of these words—they are just fancy ways to describe the exact location of the brain we are talking about

Koenigs et al., 2007

Greene et al., 2004